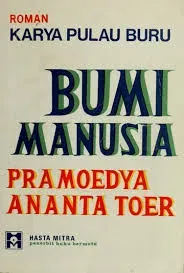

Bumi Manusia

Author: Pramoedya Ananta Toer

Category: Fiction, literature, classics

Language: Indonesian

Publication Year: 1980

Pages: 535

Description:

*Bumi Manusia* (This Earth of Mankind) by Pramoedya Ananta Toer is one of those books that feels like you’re about to witness history come to life. Set in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) in the early 20th century, the novel opens a window into the world of colonialism, social inequality, and personal identity. But don’t think of it as just another historical novel—it’s a love story, a political statement, and a philosophical reflection all rolled into one.

The protagonist, Minke, is a Javanese student who is stuck between two worlds. He’s from a native family but has received a European education. That mix of influences makes him a very interesting character. On the one hand, he’s critical of the way colonial powers treat the indigenous population; on the other, he can’t help but be influenced by the Western ideals of freedom and individualism. Minke's perspective gives readers a chance to explore the cultural clash at the heart of the story.

Early on, Minke meets Nyai Ontosoroh, a concubine who is probably one of the most compelling characters in Indonesian literature. She's a strong, intelligent woman, trapped by society's rules yet defying them at every turn. As a concubine, she’s looked down upon, but Nyai manages her own business and proves to be far more capable than most of the male characters. It’s through her that Minke begins to see the hypocrisy of colonial society.

Then there’s Annelies, Nyai’s daughter, with whom Minke falls in love. Their romance is tender but also tragic. Annelies represents innocence and fragility in a world that is anything but kind to women like her—mixed-race children of concubines. Colonial law sees her as neither fully Dutch nor fully Javanese, which creates problems down the line. It’s heartbreaking to watch their love story unfold under the weight of social, legal, and racial pressures.

Pramoedya’s writing is deeply human, filled with rich descriptions and sharp insights into the injustices of the time. What makes it even more powerful is that *Bumi Manusia* isn’t just fiction; it mirrors the real struggles faced by Indonesians under Dutch rule. Minke’s story is essentially Indonesia’s story, as the country grapples with its identity and future. You’ll get glimpses of a growing nationalist sentiment and the early sparks of rebellion.

But don’t worry, it’s not all political philosophy. Pramoedya manages to weave humor and warmth into his characters’ interactions, especially in the way Minke and Nyai banter. Minke’s occasional naivety contrasts beautifully with Nyai’s world-weariness, creating moments of levity in an otherwise heavy narrative.

It’s impossible to talk about *Bumi Manusia* without mentioning the way Pramoedya wrote it—while imprisoned by the Indonesian government without access to writing materials. The novel was originally part of an oral storytelling tradition, dictated to fellow prisoners before eventually making its way to paper. Knowing this gives the book an added weight; it’s a story about resistance, not just against colonialism but also against oppression of all kinds.

One of the novel’s greatest strengths is how it refuses to present clear-cut heroes and villains. The Dutch aren’t all evil, and the natives aren’t all innocent. The story presents a nuanced look at the complexity of human relationships within a brutal system. Even Minke, who is our hero, has his flaws—he's occasionally self-absorbed and slow to understand the plight of the women in his life. It makes him real, relatable, and frustrating in equal measure.

For all its historical context, *Bumi Manusia* feels timeless. Its themes of power, love, and freedom resonate across cultures and eras. Whether you're familiar with Indonesian history or not, you’ll find yourself rooting for Minke and his struggle to define his own identity in a world that’s determined to do it for him.

In the end, *Bumi Manusia* doesn’t offer easy answers, but it does leave you thinking long after the final page. You’ll feel frustrated by the injustices, warmed by the love story, and in awe of Pramoedya’s ability to turn a tale of colonial-era Indonesia into something universal. Plus, if nothing else, you’ll come away with a whole new appreciation for strong female characters like Nyai Ontosoroh, who quietly steal the show.

Personal Notes:

I read this book in the 1990s while Soeharto's regime banned it. The young nowadays must be grateful that they can easily find and read this book.

Back to Home