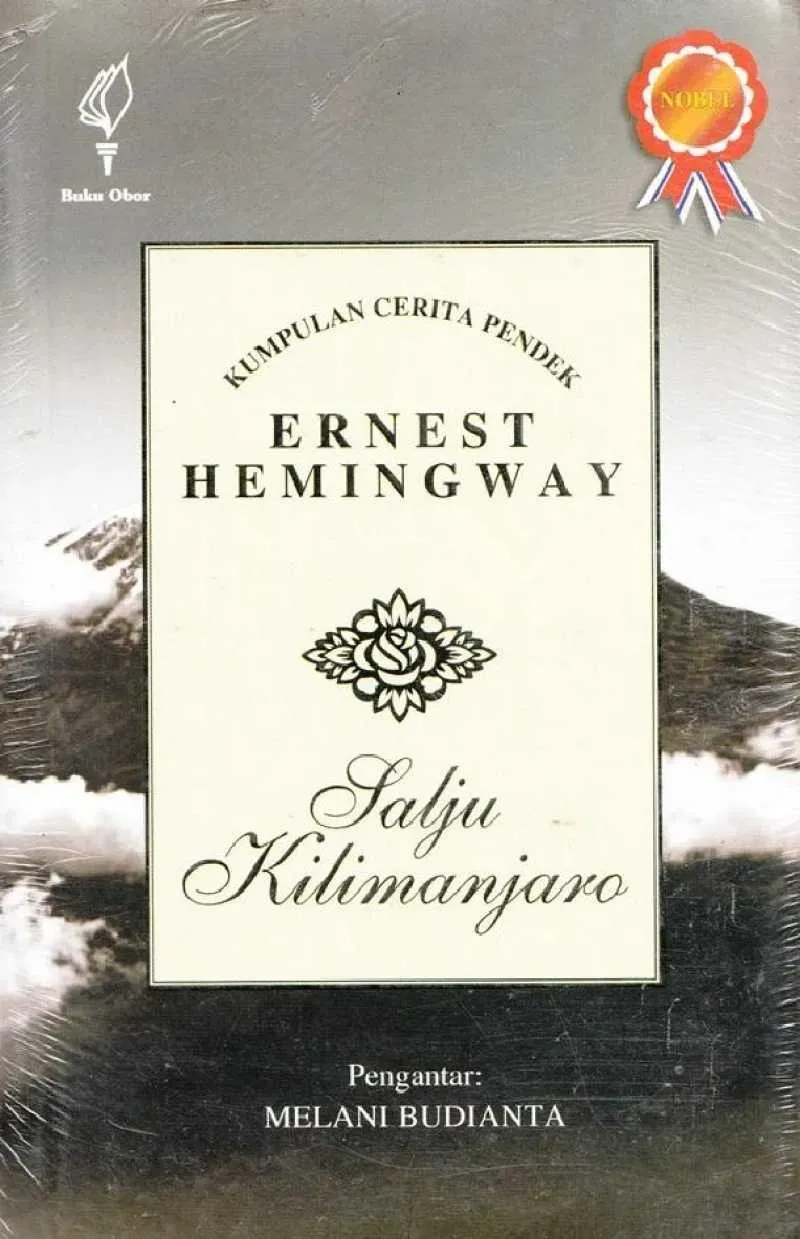

Salju Kilimanjaro

Author: Ernest Hemingway , Ursula G. Buditjahja (Translator)

Category: Fiction, literature, classics

Language: Indonesian

Publication Year: 1997

Pages: 315

Description:

*The Snows of Kilimanjaro* by Ernest Hemingway is a collection of short stories that showcases the range of themes and emotions Hemingway is known for. If you’re familiar with his style—concise, sharp, and straight to the point—this book feels like a natural extension of his other works. The collection explores big themes like death, war, regret, complicated love, and adventure, all presented in Hemingway's trademark stripped-down prose, where simplicity on the surface belies the emotional depth underneath.

The most famous story in the collection is *The Snows of Kilimanjaro*, which tells the tale of a writer named Harry who is dying from an infected wound while on safari in Africa. The story is saturated with regret, particularly about wasted time and all the things Harry never wrote. This isn’t just about his physical death—it’s about the death of his creativity and potential. Kilimanjaro, the majestic mountain in the background, becomes a symbol of the ambitions and dreams he never reached. As Harry lies dying, his wife Helen stays by his side, trying to care for him, but her presence only seems to aggravate him. Their relationship, full of unspoken tensions, reflects one of the key dynamics Hemingway often explores in his stories—love that is fraught with emotional distance and confusion.

But the collection isn’t just about Harry and Kilimanjaro. There are other gems, like *The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber*, which tells the story of a man who, ironically, finds his courage at the very end of his life. It’s a touching exploration of self-discovery under pressure, set against the backdrop of an African safari. Themes of masculinity, pride, and bravery take center stage here, and Hemingway delivers the story with a clever sense of irony—Macomber’s brief moment of happiness and triumph comes right before tragedy strikes. The tension in this story is palpable, highlighting the unpredictable nature of life and how fleeting significant moments can be.

While *The Snows of Kilimanjaro* leans more towards melancholy, there are stories like *The Gambler, the Nun, and the Radio* that inject a more subtle sense of humor. This story is lighter in tone but still tackles serious themes like faith, luck, and how people cope with suffering. Hemingway introduces characters who are trying to find meaning in the chaos of their lives, and while the dialogue and scenes may seem ordinary at first glance, there’s often a deeper message woven into the mundane.

Then there are war stories like *In Another Country*, which delves into the physical and emotional scars left by World War I. Hemingway frequently explored the trauma of war, and here you get a sense of the alienation and emptiness that follows. The protagonist is an American soldier undergoing physical therapy in Italy, but there’s a rift between him and the other soldiers, who feel he doesn’t truly understand their suffering. This story taps into the broader feeling of isolation often experienced by war veterans, who struggle to reconnect with the world around them.

Hemingway’s minimalist yet impactful writing style shines throughout the collection. He never wastes words, and his descriptions are always precise. It’s this economy of language that allows the emotional intensity of the stories to emerge without being overdone. Hemingway doesn’t spell everything out for the reader—he leaves a lot unsaid, and it’s in the subtext where the real emotional weight can be found.

Overall, this collection demonstrates Hemingway’s mastery in exploring the fundamental issues of human life: death, regret, war, love, bravery, and fleeting happiness. While some of the stories may feel slow or somber, Hemingway always pulls you into the world of his characters. The book is perfect for readers who enjoy reflective, thought-provoking stories, but told in a deceptively simple way. Hemingway doesn’t offer easy answers or solutions to the existential questions he raises, but he invites readers to sit with those questions and reflect on them just as his characters do.

Personal Notes:

Some reviewers have expressed concerns about this version's Indonesian translation, but everything is fine for me. I can still enjoy the nuances Ernest Hemingway intended to convey.

First published January 1, 1936. The Indonesian version was published on May 1, 1997, by Yayasan Obor Indonesia.

Back to Home